A Fresh Look at Steering Geometry

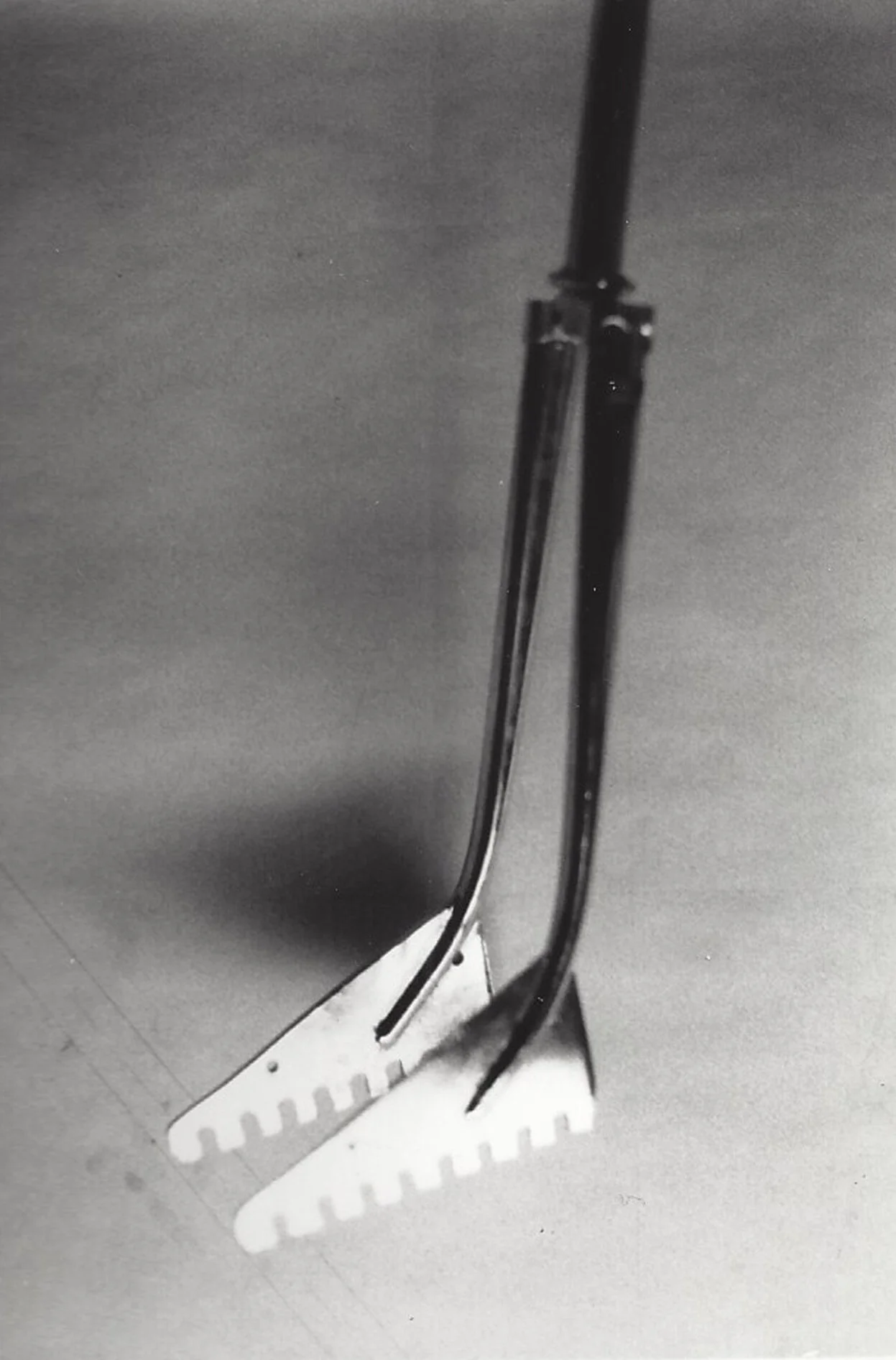

Crazy fork thingamajig

The following is a revision of an article published in CYCLING USA, February 1981. Although the references are dated, the basic concepts are still valid.

By Chris Kvale and John Corbett

It’s the motor that counts, of course, but a bicycle frame that gives optimum handling characteristics for a given event will increase efficiency and, therefore, performance. One area of frame design which has often been misunderstood because of lack of information, misinformation, and general confusion is front-end design—specifically the relationship between head angle and fork offset. With the advent of high-quality American-made frames available throughout the country, it is important for the rider to understand some of the factors which will affect his choices in geometry. The following discussion, based on several years of secondary and original research, will illustrate the complexity of the problem and lead to some tentative conclusions.

Current References

The most frequently repeated myth regarding head angle and fork offset is the notion that “neutral” steering, thought to be ideal, could be described by a formula which relates them to trail, resulting in a frame in which the top of the head tube neither rises nor falls as the wheel is turned. A formula developed by A.C. Davison was published in the British magazine CYCLING in 1935. He had discovered that when rake (offset) equals trail, the frame does not rise or fall when the wheel is at 90º; he assumed that the frame was not rising or falling while the wheel is being turned. However, the frame does rise or fall while the wheel is being turned to the 90º position, and this can be proven mathematically. At 73º, the Davison formula would give an offset of 50.8mm; with this offset, the frame would drop 3.65 mm at the 60º point. In fact, the front of the frame will always drop unless the offset is far longer than would ever be used; i.e., at 73º, an offset of 104 mm would be required—at this point the frame doesn’t fall, it rises. With all steering geometries of practicable design, the frame will drop as the wheel is turned. However, the most important point to understand about the Davison formula is that its relationship to “neutral” steering is purely coincidental. In the 1930’s head angles were flatter and the Davison formula seemed to give a satisfactory explanation for a very stable feeling frame. For example, a frame with a head angle of 71º and an offset of 57 mm, the trail of 57 mm would give this frame a very stable feeling which some riders might describe as “neutral.” However, with 74º, a fork offset of 48 mm yields 48 mm of trail, and most riders would find this a little on the sensitive side and far from what would be described as “neutral.” The fact is that the amount of trail by itself seems to be the primary operative factor affecting steering and the Davison formula would vary the trail much more than experience indicates, especially with steeper head angles.

The fact that bicycle design is an incredibly complicated subject is well illustrated by David Jones in PHYSICS TODAY (April 1970). Using a computer and advanced mathematics, Jones has probably produced the most accurate and authoritative formulas governing bicycle design, and amongst other things, disproved the myth of the magic formula for head angle and fork offset which results in a frame which neither rises nor falls as the wheel is turned. He also makes the point that it is impossible to attempt to isolate one factor of frame design from the others and predict changes in performance and handling by dealing with that single factor.

In their authoritative book BICYCLING SCIENCE: ERGONOMICS AND MECHANICS (MIT Press, 1974), Frank Whitt and David Wilson treat steering geometry with a page and a half and one table, an indication of the paucity of information on the subject. However, they do stress the extremely important point that the person-machine relationship is so complex and so variable that mathematical models and absolute statements are, at very best, only a rough guide.

Unfortunately, myths die hard. The Davison formula continues to pervade recent references on frames and frame designs. Some authors mention it by name, others referring to it but without discussing it all. Adding to the confusion surrounding the topic, some authors have introduced the ill-defined terns “understeer” and “oversteer.” Generalities abound: “…steep head angle and short fork rake result in quick and nervous handling…,” “…if the angle is too steep and the rake is very short, the steering will be ultra-sensitive…,” and “…a longer rake will tend to be more stable…” A lot of the current references seem to be repetitions of long-held but unsupported beliefs. However, the fact that something is amiss is recognized in that at least two of the current authorities realize that “neutral” steering does not seem to fit today’s frames: one suggests that “oversteer” is desirable for a racing frame and the other observes that “the trend is away from the neutral or near-neutral steering geometry of the past.”

Original Research

The reader should keep in mind four important points during the following discussion: (1) The research and conclusions are based on middle-sized frames, about 52 to 62 cm and that frames towards the ends of this range are more difficult to design to accommodate the rider’s body while maintaining desired handling characteristics. (2) As some of the far-sighted authors have noted, this is a complex situation and no one factor should be totally isolated. (3) The conclusions are made for normal riding speeds; at very low speeds, trail does not seem to have the same effects. (4) The research and conclusions are based on unloaded racing frames and do not apply to loaded touring frames.

As indicated by the trend of the previous research, the relationship between head angle and fork offset, resulting in trail, is probably the most important factor in determining the steering characteristics of a frame. The other factors which appear to have some effect are, in no particular order, bottom bracket height. front wheelbase (bottom bracket to front axle), overall wheelbase, and the resulting weight distribution.

One of the first thing Corbett and I (Kvale) did was to accurately measure six frames with which I was intimately familiar. Three were Italian—a Cinelli road frame, a Masi road frame, and a Cinelli pursuit frame; three were American—a custom track frame, a custom criterium frame, and the first frame I built. I found that the two frames which gave the greatest hands-off stability were the track bike and my frame; both of these frames have a fork trail in the low sixties. The Cinelli and Masi road frames, with trail in the high forties steered lightly and easily, but neither was exceptionally easy to ride no-hands. The Cinelli pursuit frame I rode several years on the road as five-speed time trial bike; it was extraordinarily stable no-hands but very heavy in the corners—seeming to require actual physical steering than mere leaning. It is important to note that this bike handles perfectly in its event—steady track time-trialing; it has a large amount of trail which makes it easy to stay right on the pole line without wandering around the sponges. Although the American-made criterium frame had the right amount of trail to predict stability and ease of no-hands riding, it was squirrelly—even hands-on. The problem was, I think, that the top tube was too short and the short front wheelbase moved the center of gravity so far forward that it had an adverse effect on steering.

From these and many other bikes I’ve ridden, I’ve come to the conclusion that the optimum trail for a racing or sport frame should be in the high fifties to low sixties. I would describe this trail as giving stability which enables the bike to be ridden easily under the most adverse conditions—crosswind and uneven road surface—but still allows a feeling of agility in steering. This kind of stability tends to keep the front of the bike from wandering around which requires energy to correct regardless of whether the rider is aware of it and would contribute to fatigue in a long road race or ride. This stability also enables the rider to easily take a hand off to reach in a pocket, grab a bottle, look over his shoulder at traffic, and so forth, while keeping the bike in the same line.

Since constant trail can be maintained while juggling the head angle and fork offset, it is necessary to understand what effects those two factors have with constant trail. Flatter head angles (72-73º) require a longer fork offset to maintain trail; this combination is more comfortable on rough roads, but does not seem to sprint or climb as well as a steeper head angle-less offset combination since the wheel is farther in front of the rider. In out-of-the-saddle sprints, the front wheel seems to go side-to-side with each leg thrust than with the latter combination. On the other hand, the steeper (74º-75º) head angle-less offset puts the wheel more underneath the rider. In a violent sprint, this combination seems to have a feeling of pivoting and going less far from side-to-side with each leg thrust. The trade-off, of course, is comfort. The steeper angle/less offset will transmit more road shock to the rider’s body with consequent fatigue. For a rider who wants a frame for most road events a compromise of 73 1/2º seems to be adequate for criteriums without being unnecessarily fatiguing in long road races. Many riders specializing in shorter events feel that compromises for the sake of comfort are unnecessary, but they should remember that a frame which contributes to fatigue probably diminishes performance.

Although head angle and fork offset combination affect comfort, it also important to realize that the type of materials with which the frame is made may have an effect on feel and handling, especially on rough roads or in a sprint. For instance, a fork made of Reynolds 531 narrow oval tubing (old style) with a standard fork crown would probably flex much more side-to-side in an out-of-the-saddle sprint than would a fork of identical geometry made of Columbus SP (comparable wall thickness) with an investment cast crown.

It is a mistake to attempt to judge the amount of fork offset by sighting the fork from the side. Many Italian frames made with Columbus tubing appear to have little fork offset, but this is an optical illusion caused by a very gradual curve of the fork blade as supplied by the Columbus factory. Some of the curves in the Reynolds blades supplied by the factory are much sharper, and a fork built these could appear to a lot more offset than they actually do.

The question then is, why do the Italians build frames with steep angles and relatively large fork offsets with consequent little trail? (Colnagos are often 74-75º, 50 mm fork offset, and low forties trail). It seems that the bottom bracket height contributes to—and complicates—the problem of stability. Most Italian racing frames have medium-low bottom brackets, usually 70 mm drop—about 10.55 inches from the ground, and it is probably this fact which helps compensate for the relative lack of trail. Nonetheless, most of these frames are still a little on the nervous side and tend to wander a bit when one’s attention is taken off the front. Most of them are more difficult to ride no-hands under adverse conditions than many American frames, which tend to have shorter top tubes and less fork offset. This again illustrates the interdependence of all aspects of frame geometry and raises another important question: how does a frame with sold no-hands stability still handle quickly? Keeping the overall length of the frame down, especially the front wheelbase, seems to promote quick handling. It is very important at this point to distinguish between “light” feeling and responsive handling. A frame with fork offset in the high fifties to low sixties will be more stable yet still be responsive without being nervous if the top tube is relatively short in proportion to the rider’s torso.

An interesting illustration of this point was made with a homemade frame which Corbett repaired. Since the front triangle had to be removed from this frame, the owner decided that this was the time to shorten the top tube, and Corbett shortened the top tube by 4.5 cm! The head angle and fork offset were maintained, but the new shorter frame differed markedly in its handling, becoming more responsive.

One of the other experiments Corbett performed was to build and ride a fork with and adjustable wheel position. By fixing the head angle and changing the fork offset in 18 mm increments, he was able to ride one of his bikes with trail from -27 mm to 110 mm and to evaluate its steering characteristics. He found that the steering characteristics fit into the pattern described above: i.e., with a trail of less than forty the bike felt nervous; with a trail of 53 mm it began to exhibit the sort of hands-off stability which seems desirable yet still turns easily, and with a trail of 72 mm it had a very heavy feeling. Again, it is important to note that the weight distribution will change as the wheel is moved in the fork, and this probably has an effect in addition to the difference in trail.

With all this in mind, are there any conclusions which can be drawn which would be useful? The answer is probably yes; it seems that for middle-sized frames, the head angle/fork offset combination which gives a trial in the high fifties to low sixties will give a no-hands stability which is desirable for a racing or sport frame. The angle will be chosen for the event, but it quite possible to make an entirely satisfactory compromise.

The authors: Chris Kvale raced from 1965 through l987 and has been building custom racing, sports, and touring frames since 1976. John Corbett, who taught mathematics at the University of Minnesota, built a number of custom frames and studied frame design intensively at the time this article was written, in 1980.